5 Steps to Exploit a Critical IDOR Vulnerability in Webhook Deletion

Critical IDOR Vulnerability in Webhook Deletion – A Real-World Exploitation Guide

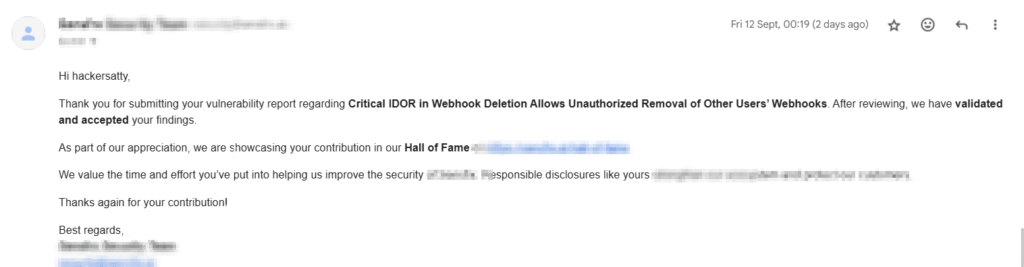

When testing web applications, one of the most common but high-impact issues I encounter is Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR). In this blog, I will walk you through how I discovered a Critical IDOR vulnerability in a webhook deletion functionality on my testing platform (hackersatty.com).

This post is a complete breakdown of how I identified the vulnerable endpoint, exploited it, and demonstrated real-world impact — all while following responsible testing practices.

What is an IDOR Vulnerability?

Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR) is a type of access control vulnerability where an application exposes internal identifiers (like user IDs, webhook IDs, or document IDs) without properly checking if the user is authorized to access them.

In simple terms: if you can change an id in a request and access or delete something that belongs to another user, the application is vulnerable to IDOR.

Why IDOR in Webhook Deletion is Critical

Webhooks are essential for integrating systems — they send automated updates and notifications between platforms.

Now, imagine a situation where any user can delete another user’s webhook. This means:

-

Service disruption

-

Loss of customer integrations

-

Denial of important notifications

-

Direct impact on business operations

That’s why Critical IDOR vulnerability IDOR in webhook deletion is classified as Critical.

Reconnaissance – Finding the Endpoint

During my testing on hackersatty.com, I followed a systematic process to identify the vulnerable endpoint:

-

Create an account (Account A) and explore available features.

-

Enable developer tools (browser DevTools or Burp Suite) to capture requests.

-

Create a webhook → noted down the request and observed an

idparameter. -

Saw that the webhook deletion was performed via:

-

Registered another account (Account B).

-

Repeated the same process to create a webhook, confirming that each webhook had a unique

id.

This made me suspect that simply changing the id might allow cross-account access.

Step-by-Step Exploitation

Here’s how I reproduced the issue:

-

Account A creates a webhook → assigned

id=15120. -

Captured the deletion request:

-

Account B creates its own webhook → assigned

id=15122. -

Using Account B’s session, I replayed the captured deletion request.

-

Modified the request to target Account A’s webhook ID (

id=15120). -

Result: Account B successfully deleted Account A’s webhook.

Proof of Concept (PoC)

Request (Attacker – Account B deleting Account A’s webhook):

Response:

✔ Confirms that Account B deleted Account A’s webhook without authorization.

Reference: HackerOne’s Guide to Broken Access Control.

Impact Analysis

The vulnerability directly affects integrity and availability of the application:

-

Any user can delete webhooks of others.

-

Attack requires no elevated privileges — just a free account.

-

Real-world consequences: service disruptions, broken integrations, loss of business data.

Severity Assessment (CVSS v3.1)

-

Attack Vector (AV): Network

-

Attack Complexity (AC): Low

-

Privileges Required (PR): Low

-

User Interaction (UI): None

-

Scope (S): Changed

-

Integrity (I): High

-

Availability (A): High

Score: 9.1 (Critical)

Recommendations to Fix Critical IDOR vulnerability

-

Enforce proper authorization checks – Verify that the user owns the webhook before allowing deletion.

-

Use Object-Level Access Control – Implement strict checks for every request modifying user resources.

-

Avoid predictable identifiers – Use UUIDs instead of sequential numeric IDs.

Final Thoughts

This case study demonstrates how a simple oversight in access control can lead to a Critical IDOR vulnerability.

By following a structured approach — from endpoint discovery, testing unique IDs, to replaying requests — I was able to identify a severe issue that impacts the core integrity and availability of the application.

For developers, the lesson is clear: never trust client-side input and always enforce authorization checks at the server level.

For security researchers, this highlights why IDOR remains one of the most dangerous yet common vulnerabilities.